CPABC recently released BC Check-Up: Work, its third economic report of 2022.1 The report examines the employment trends that emerged in the province over the past year and compares the data to pre-pandemic levels

BC Check-Up: Work report looks at emerging employment trends amid economic turmoil

As was the case in 2021, the results in 2022 were mixed.2 BC’s labour market recovered quickly over the past two and a half years—in fact, more quickly than labour markets in most other Canadian regions—but its labour shortage has continued to grow. And while BC’s unemployment rate fell to levels not seen since 2019, the job vacancy rate3 reached record highs. Adding to the complexity is the slowing of employment growth in recent months, as mounting challenges such as high inflation and rising interest rates put downward pressure on the provincial economy.

In creating the BC Check-Up: Work report, we also studied labour participation, employment recovery across sectors, and recent labour compensation trends.

Employment growth strengthened then stalled

As described in past issues of CPABC in Focus, the 2020 recession triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic was BC’s deepest economic contraction in nearly 40 years.4 By the lowest point of the recession in April 2020, more than 400,000 jobs—nearly one in every six jobs across the province—had been displaced (see Table 1), and the unemployment rate had risen to 11.5%, more than twice the pre-pandemic rates.

Table 1: Changes in Population and Employment in BC, 2019-2022

|

September 2019 |

April 2020 |

September 2021 |

September 2022 |

Change from April 2020 |

Change from September 2021 |

|

|

Unemployment rate |

4.9% |

11.5% |

5.9% |

4.3% |

-7.2 ppts |

-1.6 ppts |

|

Participation rate |

65.5% |

58.8% |

65.3% |

64.8% |

6.0 ppts |

-0.5 ppts |

|

Total employment (millions) |

2.65 |

2.23 |

2.68 |

2.75 |

23.4% |

2.6% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 14-10-0036-01 and 14-10-0287-01.

Thankfully, as restrictions eased and the global economy rebounded, BC experienced a rapid labour recovery—so rapid, in fact, that the province led the country in terms of employment gains over the past two and a half years.

BC’s total employment reached 2.75 million in September 2022, surpassing its level of employment in April 2020 by more than 520,000 job positions and even surpassing its levels of employment before the pandemic. This increase helped lower BC’s unemployment rate to 4.3% by September 2022, bringing it under the monthly average of 4.7% in 2019.

BC’s workforce grew in 10 of the past 12 months, creating a net gain of 70,400 jobs. However, between April and September 2022, job growth slowed and became more uneven due to rising inflation, higher interest rates, and other economic challenges.5 In fact, the province lost 28,100 jobs in August 2022—the largest job loss experienced by BC in a single month since early 2021—before recovering 32,900 positions in September.

Moreover, BC experienced an average monthly employment increase of 2,400 between April and September 2022, far below the monthly average of 9,400 seen between January 2021 and March 2022. It’s important to note that this recent slowdown is explained not just by emerging economic challenges, but also by the gradual lessening of the employment rebound as recovery from the deep job losses in 2020 transitioned to more typical labour market trends.

Employment and population grew at similar pace

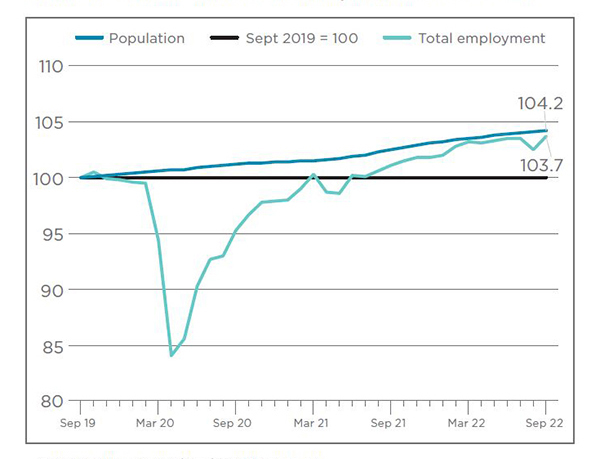

When comparing the overall employment growth of the past three years with historical trends, there is reason for optimism. Despite the significant turbulence in BC’s labour market between September 2019 and September 2022, employment growth nearly kept pace with population growth. As the BC Check-Up: Work report highlights, BC’s population grew by 4.2% over this three-year period, while the province’s total employment grew by 3.7% (see Figure 1). In turn, this job growth was critical to BC’s economic growth. Notably, however, job growth was not consistent across the board.

Figure 1: Population and Total Employment in BC, 2019-2022

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01.

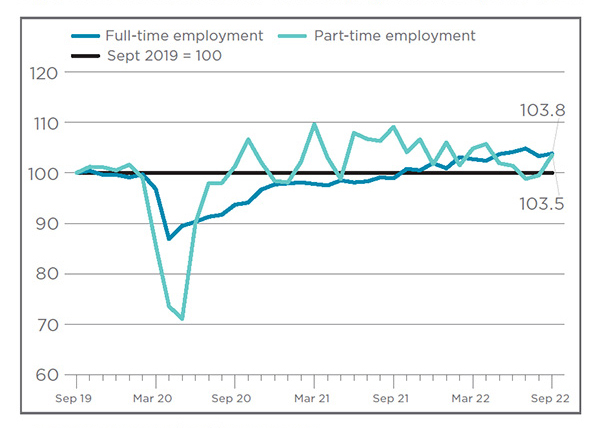

Full-time job recovery outpaced part-time

BC’s part-time workers were hit hardest by the pandemic in the early months of the crisis, as more than one in every four part-time positions had been lost by May 2020 (see Figure 2). And although part-time employment recovered more quickly than full-time employment in the latter half of 2020, full-time work is what has driven employment growth since early in 2021.

In total, there were 2.17 million full-time positions in BC in September 2022, signifying an increase of 3.8% and 4.9% from September 2019 and September 2021, respectively. In contrast, BC saw its part-time jobs decrease by 5.1% between September 2021 and September 2022. One reason for this decline is the fact that key industries with a high concentration of part-time positions, such as hospitality, struggled to recoup job losses over the past year.

Despite the recent decline, however, there were 579,200 part-time positions in BC in September 2022—3.5% more than in September 2019. This was a result of the strong recovery seen in late 2020 and early 2021.

Figure 2: Part-Time and Full-Time Employment in BC, 2019-2022

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01.

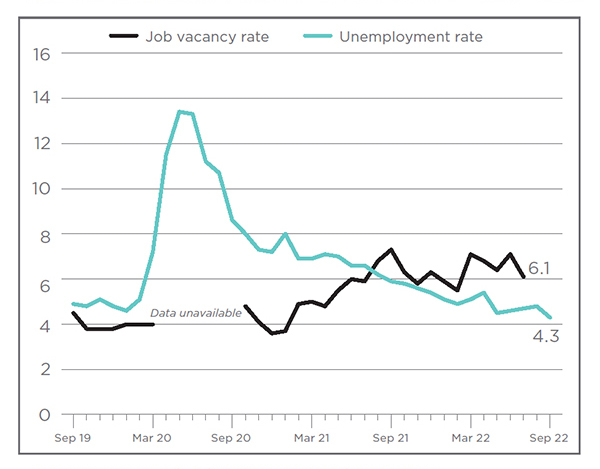

Recruitment challenges intensified

As employment recovery progressed over the past two years, both BC and Canada experienced record-level labour shortages.6

BC’s unemployment rate was down to 4.3% by September 2022, but the job vacancy rate this summer was up to 6.1%, representing 153,060 open, unfilled positions (see Figure 3). This was a significantly higher number than the 122,500 unemployed BC residents searching for work, which made it challenging for employers to attract enough staff to maximize their production of goods and services.

Figure 3: Unemployment and Job Vacancy Rate in BC, 2019-2022

Source: Statistics Canada, Tables 14-10-0287-01 and 14-10-0371-01.

This labour shortage is partly due to a decline in the percentage of BC residents actively participating in the labour market. BC’s labour participation rate7 was 64.8% in September 2022, down from 65.5% in September 2019. This seemingly small percentage change actually had significant ramifications, because if BC’s participation rate had been 65.5% in September 2022, we would now be seeing an additional 31,000 residents working or looking for work—a large pool to fill empty positions.

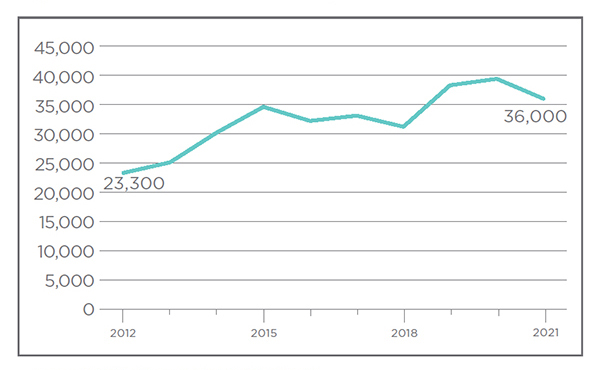

Another significant challenge for the labour market, both in BC and across Canada, has been a rapidly increasing rate of retirement.8 Between 2012 and 2021, BC saw its annual retirement numbers jump from 23,300 to 36,000, signifying an increase of 54.5% in less than a decade (see Figure 4). This growth trend is only expected to accelerate as BC’s population continues to age9—in fact, the provincial government projects that BC will see an average annual retirement rate of 63,000 between 2021 and 2031.10

Figure 4: Annual Retirements in BC, 2012-2021

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0126-01.

Service sector led job recovery, but some subsectors struggled

Although BC’s service sector initially saw more job losses than its goods sector, the former led employment recovery between June 2020 and September 2022. However, employment performance varied significantly between service subsectors during that period.

BC’s service sector workforce reached 2.25 million jobs in September 2022, up by 2.7% from the previous year (see Table 2). The strongest job growth happened in the information, culture and recreation (+17.8%), educational services (+7.5%), and professional, scientific and technical services (+6.8%) subsectors. Conversely, the following subsectors saw employment drop: business, building, and other support services (-13.6%), public administration (-4.5%), and finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (-2.2%).

Between September 2019 and September 2022, BC’s service sector workforce increased by 4.7%. Over this period, employment grew fastest in the professional, scientific and technical services (+18.3%), information, culture and recreation (+17.3%), and public administration (+13.2%) subsectors. At the same time, however, several service industries continued to struggle to return to pre-pandemic levels; these include the following subsectors: business building and other support services (-16.9%), other services such as personal and household (-9.1%), and accommodation and food services (-8.8%). These changes were consistent with those seen in service subsectors across Canada.

The downturn experienced in various service subsectors over the past two years was partly attributable to the number of Canadian workers who changed careers, with many leaving the industries hardest hit in the early days of the pandemic (such as hospitality and personal services) to enter those perceived as more stable (such as professional, scientific and technical services; and public administration).11 Collectively, this migration put significant pressure on subsectors such as food services, where many businesses struggled to find and retain talent.

Table 2: Service Sector Employment by Subsector in BC, September 2022*

|

September 2022 employment |

% change since 2019 |

% change since 2021 |

|

|

Services-producing sector |

2,254,600 |

4.7% |

2.7% |

|

Professional, scientific and technical services |

272,700 |

18.3% |

6.8% |

|

Information, culture and recreation |

151,700 |

17.3% |

17.8% |

|

Public administration |

136,000 |

13.2% |

-4.5% |

|

Health care and social assistance |

378,800 |

12.9% |

4.5% |

|

Educational services |

208,900 |

10.1% |

7.5% |

|

Wholesale and retail trade |

415,200 |

3.1% |

3.7% |

|

Finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing |

167,700 |

0.2% |

-2.2% |

|

Transportation and warehousing |

137,000 |

-5.3% |

-2.0% |

|

Accommodation and food services |

181,200 |

-8.8% |

-0.8% |

|

Other services (except public administration) |

110,300 |

-9.1% |

1.1% |

|

Business, building and other support services |

95,000 |

-16.9% |

-13.6% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0355-01.

*Subsectors have been sorted from best to worst, per percentage change since 2019.

Goods sector employment rebounded slowly

Employment in BC’s goods sector grew to 497,000 jobs in September 2022, an increase of 2.5% compared to September 2021 (see Table 3). This increase was driven by growth in three of five subsectors: construction (+10.3%), utilities (+12.8%), and agriculture (+38.3%). The remaining two subsectors (forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas; and manufacturing) experienced declines in their workforces.

Overall, the goods-producing sector failed to reach pre-pandemic levels by September 2022, with employment still down by 0.3% compared to September 2019. This failure to recover was primarily due to the fact that employment growth in the construction industry—the sector’s largest employer—remained 2.4% lower than its rate before the pandemic.

Table 3: Goods Sector Employment by Subsector September 2022*

|

September 2022 employment |

% change since 2019 |

% change since 2021 |

|

|

Goods-producing sector |

497,700 |

-0.3% |

2.5% |

|

Utilities |

16,700 |

35.8% |

12.8% |

|

Forestry, fishing, mining, quarrying, oil and gas |

47,800 |

6.7% |

-7.4% |

|

Agriculture |

28,500 |

-1.0% |

38.3% |

|

Manufacturing |

166,000 |

-1.9% |

-9.0% |

|

Construction |

238,500 |

-2.4% |

10.3% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0355-01.

*Subsectors have been sorted from best to worst, per percentage change since 2019.

Labour compensation improved, but gender pay gap persists

To help address rising prices and the tightening labour market, employers raised wages significantly over the past year. The average weekly wage in the service sector increased to $1,123, up by 5.3% compared to the weekly average in 2021. Over the same period, the average weekly wage in the goods sector increased by 8.9%, reaching $1,413.

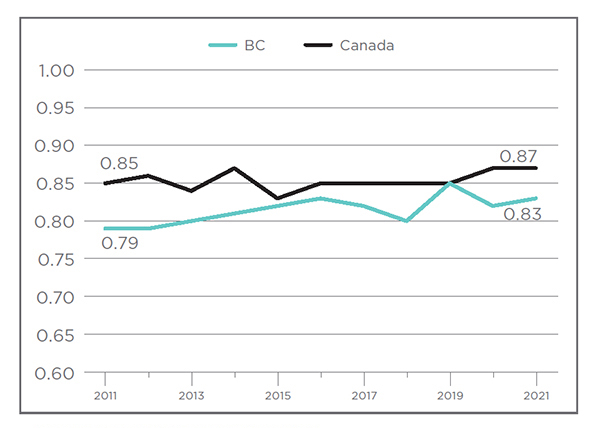

However, there was still a significant gender gap with regard to compensation, as the average female worker in BC continued to make considerably less than their male counterpart in 2021.12 The hourly wage for a female worker in BC was $25.00 in 2021 compared to $30.00 for a male worker, translating to a gender pay gap of 0.83. BC’s gender pay gap was notably wider (worse) than the gap of 0.87 for Canada as a whole, although it’s worth noting that both have narrowed slightly over the past decade (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Gender Pay Gap in BC and Canada, 2011-2021

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0340-01.

Both the federal and BC governments have started to focus on policies to make pay more equitable. For example, the federal government recently enacted the Pay Equity Act, which introduces new requirements to drive greater pay equity for federally regulated private- and public-sector organizations.13 And in the summer of 2022, the BC government held consultations for feedback on the design of new provincial pay transparency legislation.14 CPABC participated in these consultations, meeting with BC government staff in September 2022.

CPABC participates in government consultations on pay transparency legislation

To inform its development of legislation for provincial pay transparency, the BC government held consultations for feedback this summer. CPABC, represented by President and CEO Lori Mathison, FCPA, FCGA, LLB, participated in this consultation process. Speaking to the government on September 6, Mathison said CPABC believes achieving pay equity—equal pay for work of equal value—is an important societal and economic objective and supports policies that help advance this goal, including pay transparency. At the same time, however, Mathison shared CPABC’s recommendation that any new pay transparency legislation be carefully implemented to ensure that requirements are manageable for employers and to minimize any unintended consequences. She also shared CPABC’s recommendations that the new legislation should:

- Ensure new regulations are not onerous and do not reduce our competitiveness;

- Maintain flexibility so that employers can set pay based on value;

- Include a small business exemption to accommodate the unique challenges faced by small businesses; and

- Ensure employee privacy.

Employment downturn not expected, despite forecasts of a recession

There was renewed economic turmoil across the world this past year, with high inflation, rising interest rates, supply chain issues, and armed conflict casting considerable doubt on the future of the global economy. With neither Canada nor BC immune to these challenges, we’re seeing far less optimistic forecasts now than earlier in 2022. In an October 2022 update, for example, BMO Capital Markets predicts that BC’s real GDP will contract by 0.3% in 202315—a far cry from its projection of 3.7% growth in February 2022.16 Moreover, several prominent organizations, including the Royal Bank of Canada, say they believe the country will enter a recession at the start of 2023.17

However, this recession is not expected to result in a significant employment downturn. In the same October 2022 update, BMO predicts that unemployment will increase but remain relatively low—with a forecast of 6.0% for 2023 as a whole—and that employment will grow by 0.6%. The economic picture is also expected to improve over the course of 2023 as inflationary pressures ease up and interest rates decline.

Labour shortage needs to be addressed

BC is expected to face some economic headwinds over the next year, and labour shortages are expected to continue. Given the significance of this challenge for our economy, it is critical that we make augmenting the provincial workforce a top priority. This means finding ways to both encourage greater labour participation by current BC residents and to attract more new residents.

Fortunately, the province is expected to benefit from a continued resurgence of international immigration to Canada over the next two years. The federal government has set a target of welcoming 1.33 million new residents from other countries between 2022 and 2024—the largest immigration influx over a three-year period in Canada’s history.18 This influx of new residents will be a critical part of the solution.

There is also a need to further implement initiatives such as skills training programs to help British Columbians pivot to new careers, with a particular focus on those industries facing the greatest scarcity of labour. CPABC will continue to study, monitor, and report on these important policy issues, and continue to bring ideas and recommendations forward to the provincial government.

Aaron Aerts is CPABC’s economist. This article was originally published in the November/December 2022 issue of CPABC in Focus.

Footnotes

1 The first and second instalments—BC Check-Up: Invest and BC Check-Up: Live—were published in the March/April 2022 and July/August 2022 issues of the magazine, respectively.

2 Aaron Aerts, “Work in British Columbia – BC Check-Up: Work Report Looks at Emerging Employment Trends Across the Province,” CPABC in Focus, November/December 2021 (14).

3 Defined as the number of open, unfilled positions.

4 BC Stats, “BC Economic Accounts & Gross Domestic Product,” accessed September 30, 2022. BC’s 3.4% decline in real GDP in 2020 was the largest economic contraction in the province since the 1982 recession, when the province saw GDP drop by 6.4%.

5 “Bank of Canada Increases Policy Interest Rate by 75 Basis Points, Continues Quantitative Tightening,” Bank of Canada (media release), September 7, 2022.

6 Mark Wiseman and Hassan Yussuff, “Canada’s Labour Shortage Is the Country’s Greatest Economic Threat,” Globe and Mail, July 19, 2022.

7 Defined as the percentage of adults aged 15 and older who are employed or actively searching for work.

8 Josh Rubin, “New Data Shows 50% Jump in Retirements—A Trend that’s Making the Labour Shortage Even Worse,” Toronto Star, September 13, 2022.

9 BC’s average age was 42.8 in 2021, up from 40.8 in 2011. For more details on demographic trends in BC, see “The High Cost of Living in BC,” CPABC in Focus, July/August 2022 (14-25).

10 WorkBC, BC’s Labour Market Outlook: 2021 Edition, accessed October 5, 2022.

11 Graeme Bruce and Benjamin Shingler, “In a Tight Labour Market, This Is Where Canadian Workers Are Going,” CBC News, August 23, 2022.

12 At the time of this writing, the most recent data available was from 2021.

13 Employment and Social Development Canada, “Overview of the Pay Equity Act.”

14 Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Labour, Developing Pay Transparency Legislation (discussion paper), June 2022.

15 BMO Capital Markets, “Cold in the Forecast,” Provincial Monitor, October 5, 2022.

16 BMO Capital Markets, Provincial Economic Outlook for Feb 4, 2022, February 4, 2022.

17 Claire Fan and Nathan Janzen for RBC, “Proof Point: Canada’s Economy Is Headed for a Recession,” July 7, 2022.

18 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, “Notice – Supplementary Information for the 2022-2024 Immigration Levels Plan,” February 14, 2022.