“The collapse of Enron was devastating to tens of thousands of people and shook the public’s confidence in corporate America.”1

—Former FBI Director Robert Mueller

On December 2, 2001, Enron Inc., a high-flying energy-trading company based in Houston, Texas, collapsed amid one of the largest cases of accounting fraud in history. Enron’s bankruptcy that day ruined many lives, led to the demise of one of the world’s largest accounting firms, and triggered the most significant changes in the accounting profession in 100 years.

This article reviews the root causes of the Enron scandal and outlines some of the biggest lessons learned.

What happened?

After the deregulation of electrical power markets in the southern United States in the 1980s, Enron became an energy broker trading electricity and other commodities. Its modus operandi was to enter into one contract with an energy seller and a different contract with an energy buyer, and then make money on the difference between the selling price and the buying price. Enron kept these records closed, making it the only party aware of both prices. This system was immensely profitable, and over time, Enron began to design increasingly varied and complex contracts. As its services became more complex and its stock soared, Enron created a group of partnerships (a form of business which we now call variable interest entities) that allowed managers to shift losses and debt off their books—further increasing Enron’s recorded profits.2

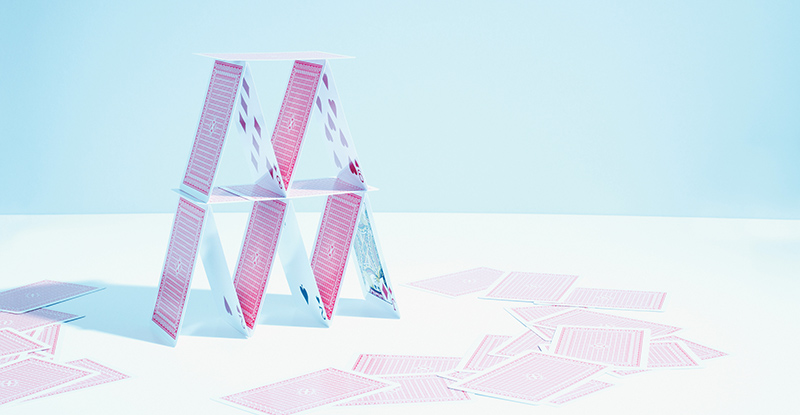

By the late 1990s, Enron had become a darling of Wall Street. Its executives became multimillionaires by exercising stock options as Enron’s stock price increased.3 Fortune magazine named Enron the most innovative company for several years’ running.4 What Wall Street did not know—until it was too late—was that Enron was a house of cards, and its profits merely a mirage.

The house of cards began to collapse in 2001 as the US economy began turning downward. Sherron Watkins, an American CPA and vice-president of Enron, sent a memo to the company’s founder and then-CEO Ken Lay expressing her concern about the accounting for the partnerships, saying she was “incredibly nervous that we will implode in a wave of accounting scandals.”5 Watkins later discovered that instead of investigating her concerns, Lay consulted Enron’s lawyers about how to fire her.6 The firing never happened, but the implosion did. Only weeks after Watkins sent her memo—and after 20 years of consistent quarterly profits—Enron shocked the market by announcing a $544-million loss.7

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission subsequently launched an investigation, and two months later, Enron declared bankruptcy. Three weeks before their winter holidays, most of Enron’s 21,000 employees were suddenly terminated—with neither severance nor health insurance.8

Where were the auditors?

The swift collapse of such a seemingly successful company naturally led the public to ask: Where were the auditors? Enron’s auditors were Arthur Andersen LLP9—at the time, the fifth-largest accounting firm in the world. As reported in the Chicago Tribune, a high degree of trust had been built up between the two organizations, and it was commonplace for Enron to hire Arthur Andersen staff into its accounting team: “Alberto Gude watched it all play out on the 44th floor. As vice-president of information systems for Enron Corp., Gude worked for Rick Causey, a former Andersen audit manager who had become Enron’s chief accounting officer. Gude’s department shared the floor with Andersen’s new team of internal auditors. ‘All of a sudden your independent auditor was your internal auditor, and probably right there you had a conflict.’”10

The Wall Street Journal also reported on the close relationship between the energy giant and the accounting firm, saying: “Andersen auditors and consultants were given permanent office space at Enron headquarters here and dressed business-casual like their Enron colleagues. They shared in office birthdays, frequented lunchtime parties in a nearby park and weekend fund-raisers for charities. They even went on Enron employees’ ski trips to Beaver Creek, Colo. ‘People just thought they were Enron employees,’ says Kevin Jolly, a former Enron employee who worked in the accounting department. ‘They walked and talked the same way.’”11

Arthur Andersen performed a host of then-permissible—and more profitable—non-audit engagements for Enron, in addition to its assurance work, and by 2001, the firm’s total annual fees from all Enron engagements were US$52 million, divided almost equally between auditing work and consulting services.12 Regarding Arthur Andersen’s actions, Lynn Turner, former chief accountant of the Securities and Exchange Commission, mused, “One has to wonder if a million bucks a week didn’t play a role.”13

Were there warning signs?

Writing for Fraud Magazine,14 Watkins said there were warning signs at Enron that should have alerted observers to a problem. These included:

- State of risk management – Enron’s internal audit function was weak (fully outsourced), with little authority to affect corporate change. The Audit Committee was ineffective and rarely involved itself in risk management.

- Tone at the top – Enron’s CEO engaged in a number of questionable ethical practices. His abuse of authority included requiring all staff to book their corporate travel through his sister’s travel agency.

- Stock option overuse – Enron used stock options to reward employees through an increasing share price. Overusing this method incentivized short-term behaviours that harmed long-term corporate strategy.

- Diffusion of responsibility – Many of Enron’s transactions were so complex that few employees or board directors could actually understand them. Only a small number of individuals were fully aware of the financial ramifications of the company’s transactions.

- Exceptions to the rules allowed – Enron prioritized profitability over ethics when reviewing employee behaviour. Profitable employees received only minor disciplinary action when ethical lapses were detected.

- Impeded internal communications – There was no clear path for employees to take ethical concerns to management and no robust whistleblower function.

- Internal conflicts of interest – Enron’s board of directors knowingly enabled CFO Andy Fastow to enter into a fraudulent investment partnership that enabled Enron to boost its earnings.15

Watkins said she first noticed signs of fraud in 1996, five years before it was exposed.16 “The warning signs of fraud were there in 1996, and I now take those much more seriously than I did back then,” she said in a 2007 interview in Ethix magazine. “In 1996, I simply protested, got nowhere, and switched divisions.” Watkins added that she should have “made an even bigger deal about it” at the time.17

After the fall

The consequences of Enron’s collapse were swiftly felt. The U.S. Department of Justice charged and obtained convictions against 21 individuals, including Lay’s successor as CEO, Jeffrey K. Skilling, who was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment (the conviction against Lay himself was dismissed because he died before sentencing). Many of these individuals were accused of conspiracy to conceal Enron’s fraudulent transactions from shareholders and Arthur Andersen.18

A few months after holding hearings on the scandal, the US Congress passed the Public Company Accounting Reform and Investor Protection Act of 2002—a major legislative reform more commonly known as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (Sarbanes-Oxley). With Sarbanes-Oxley came the establishment of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, which made auditors of American public companies subject to government oversight for the first time in US history.19 Sarbanes-Oxley also substantially reformed the role of auditors in public company audits by prohibiting many of the kinds of close relationships that existed between Enron and Arthur Andersen.

As for Arthur Andersen itself, the firm was charged with obstruction of justice when Arthur Andersen’s engagement partner instructed his staff to shred any documents they considered unnecessary for their audit working papers. Ultimately Arthur Andersen was cleared of this charge by the United States Supreme Court, but the resolution came too late to save Arthur Andersen’s reputation and business, and most of its 28,000 worldwide employees also lost their jobs. More than 1,200 public companies in the US (and countless more worldwide) suddenly had to find a new auditor after Arthur Andersen stopped auditing public companies.20

With Sarbanes-Oxley also came the mandate for significant changes to generally accepted accounting principles for variable interest entities—the kind of vehicles that had enabled Enron to hide its losses for years. In 2003, the US Financial Accounting Standards Board implemented these changes.21

How Canada responded

As the Enron scandal unfolded south of the border, government regulators and the accounting profession in Canada realized that important reforms were needed to prevent a similar situation from happening here. Significant changes followed, including:

- The establishment of the Canadian Public Accountability Board (CPAB) – The CPAB was created by Canada’s securities regulators to assess the audit quality of firms that perform public company audits in Canada. Under securities rules, any CPA firm that audits a public company must register with CPAB and adhere to CPAB’s findings.

- Amendments to auditor independence – Major amendments were made to the rules of professional conduct22 for accounting professionals to ensure the independence of public company auditors. In particular, Rule 20423 of what is now the CPA Code of Professional Conduct (in BC, the CPABC Code of Professional Conduct) was greatly enhanced to cover issues such as:

- Evaluating threats and safeguards to auditor independence;

- The provision of non-assurance services by auditors;

- Contingent fees;

- Audit team rotation – long association of senior audit personnel;

- Prohibited relationships; and

- Gifts and hospitality.

- New guidance on accounting standards for variable interest entities – In 2009, Canada’s Accounting Standards Board introduced a guideline that provided guidance on consolidation principles when accounting for the results of variable interest entities. This guidance, which was subsequently consolidated into section 1591 (Subsidiaries) of the CPA Canada Handbook, ensures that the results of appropriate entities are consolidated to accurately present a consolidated entity’s financial situation.

Lessons reflected in the CPA Code today

Rule 205 (False or misleading documents and oral representations) of the CPABC Code of Professional Conduct (CPA Code) states that a registrant24 must not:

“(a) sign or associate with any letter, report, statement, representation or financial statement which the registrant knows, or should know, is false or misleading, whether or not the signing or association is subject to a disclaimer of responsibility, nor

“(b) make or associate with any oral report, statement or representation which the registrant knows, or should know, is false or misleading.”

While the guidance to Rule 205 recognizes that certain circumstances may place a registrant in a difficult position with their employer or client, it requires the registrant to draw a clear line. Accordingly, in complex situations, registrants are advised to consider obtaining legal advice.

What about whistleblower protections?

We discussed the requirements of the CPA Code with respect to confidentiality in the November/December 2021 issue of CPABC in Focus (page 30), and plan to pick up the thread in a future article, particularly as there is an ongoing debate in Canada and elsewhere about the need for and extent of whistleblower protections in accounting and other professions.

Need guidance?

The guidance in the CPA Code explains how the rules should be applied. CPABC’s professional standards advisors are also here to help. You can consult them for confidential guidance to ensure that you stay compliant with the CPA Code when navigating difficult situations.

Contact our advisors by email, or call them toll-free at 1-800-663-2677.

This article was originally published in the March/April 2022 issue of CPABC in Focus.